|

|

|

International Journal of Academic

Library and Information Science Vol. 2(2), pp. 14–21,

February, ISSN: 2360-7858 ©2014 Academic Research

Journals

Review

A

Decade of Achievement, a Call to Excellence: The History and

Contributions of the HBCU Library Alliance

Marlene D. Allen and

Shanesha R. F. Brooks-Tatum

1438 West

Peachtree NW, Suite 200, Atlanta, GA 30309, Toll Free: 1.800.999.8558 (LYRASIS).

Corresponding author’s email:

sphoenix@hbculibraries.org

Accepted 19

January, 2014

Many contemporary philosophers,

educators, academics, and other thinkers have begun speculating upon

possible consequences of the “digital divide,” the term used to

denote the division between people who have consistent access to

technology and those who do not. As technology continues to

transform the way we live our contemporary existences, we must also

stop and think about how it can affect our relationships with the

past. Artifacts and documents that tell important stories about our

histories can be lost forever without due diligence in properly

preserving these items. Libraries play weighty roles as preservers

of relics from the past and providers of information literacy

training. Yet, despite playing these essential roles in America

today, many libraries are threatened as state and federal

governments have decreased financial support and slashed budgets for

purchasing books, computers, and other resources. The libraries

associated with the United States’ 105 historically black colleges

and universities (HBCUs) have been especially hard-hit in these

areas for a number of reasons. Increasing numbers of African

American students opt to attend predominantly or traditionally white

institutions with the opening up of new educational opportunities;

many students also find it difficult to afford the tuition costs to

attend private HBCUs and instead must select less expensive colleges

or opt not to attend college at all.

Key Words: Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs);

HBCU libraries; African Americans; colleges; universities;

preservation; digitization; photographic preservation; training;

librarians; students; faculty; information literacy

The library is a pathway—enhancing,

extending, and supporting the academic life of an institution. It is

a catalyst in the learning process, the essential link in

scholarship and information of endless variety.

Geoffrey T. Freeman (2000).

HBCU libraries serve the unique and indispensable role as

gatekeepers of history, culture, and the African-American

experience.

HBCU Library Alliance

INTRODUCTION

These socioeconomic changes have caused many to assume that HBCUs

lack relevance in America’s seemingly “post-racial” era. Many HBCU

libraries face challenges in serving out their missions to collect

and preserve African American cultural resources and artifacts,

forcing them to devise new ways to maintain their significance and

keep up with the changing face of the American, and global, academic

landscape. Even though HBCU libraries serve as guardians of African

American cultural heritage and educators of generations of African

American students, especially in the area of information literacy,

unfortunately, there has been a lack of scholarly attention given to

the vital role that these libraries play both at their respective

institutions and in academia at large.

This article, therefore, is designed to highlight the

accomplishments of one organization, the Historically Black Colleges

and Universities Library Alliance (HBCULA). It has taken on

multifaceted challenges facing contemporary HBCU libraries in the

rapidly changing contemporary technological and academic landscape,

as well as the adapted roles that libraries must play to stay

current in these new environments. In the decade since the

organization was created in 2002 in collaboration with other groups

that have assisted the HBCULA with its work, the alliance has made

various accomplishments that have greatly impacted key areas in the

fields of library science, archival management, information

literacy, and the profession of librarianship in important ways.

This article, therefore, will celebrate the HBCULA’s achievements by

relating the history of the organization’s founding and outlining

its activities in preservation and conservation, training, and

research that make the HBCULA a significant leader in the library

world and an agent of transformation for HBCU libraries overall.

“No

Existing Organization”: The History and Development of the HBCULA

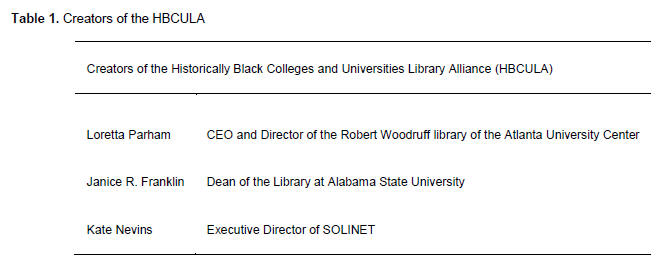

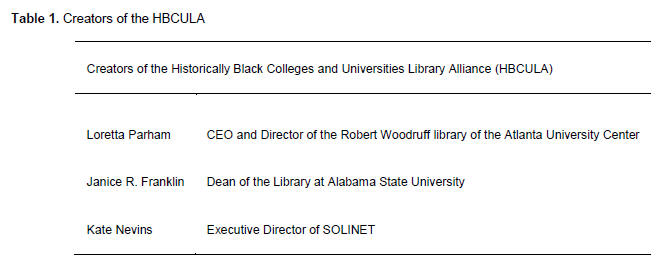

In an article entitled “The HBCU Library Alliance and SOLINET: Partners

in Inclusion,” Loretta Parham, Janice R. Franklin, and Kate Nevins, who

were all intimately involved with the creation of the HBCULA, state that

before the creation of the alliance, “No existing organization or

committee offered an agenda or venue on behalf of all of the libraries

on the designated White House HBCU Initiative; not in the American

Library Association (ALA), not in the Black Caucus of the ALA (BCALA),

not in the National Association for the Equal Opportunity in Higher

Education (NAFEO), and not in the United Negro College Fund (Parham,

Franklin, and Nevins, 2006).” Parham, former director of Hampton

University’s library, and now CEO and Director of the Robert Woodruff

library of the Atlanta University Center, and Franklin, Dean of the

Library at Alabama State University, also noticed that African Americans

were not well represented in the leadership of other library

organizations such as the Southeastern Library Network (SOLINET), where

Franklin and Parham served as the only two African American board

members from 2000 to 2004. Parham and Franklin “recognized the need for

a forearm for HBCUs” and helped bring this deficit to the attention of

the SOLINET board, especially Nevins, who was serving as Executive

Director. Because SOLINET’s geographic service area, the southeastern

part of the United States and the Caribbean, included the states where

72 percent of HBCUs are located, it was the organization that was in the

best position to support the creation of an association dedicated to

assist HBCU libraries. In May 2001, HBCU library deans and directors

representing 103 of the 105 HBCUs in the U.S. met informally to discuss

the possibility of creating a formal organization to meet the unique

needs of HBCU libraries, a response that signified the perceived need

for an alliance of this sort. By November 2001, these deans and

directors had inaugurated an electronic discussion list to foster

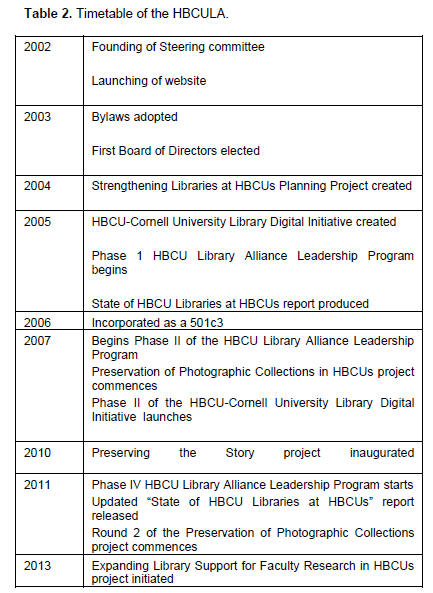

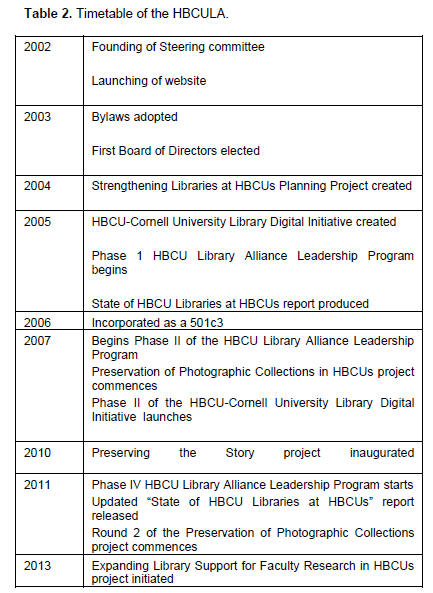

communication and share ideas amongst institutions. Table 1.

Another crucial step to the alliance’s creation was made when a steering

committee was formulated, consisting not only of Parham and Franklin,

but also Emma Bradford Perry, Elsie Stephens Weatherington, Tommy

Holton, Merryll Penson, Jennifer Bliss, and Kate Nevins. This committee

formed in January 2002 and began soliciting support from HBCU land grant

institutions and encouraging their participation in the formation of the

HBCU Library Alliance. The committee made another important achievement

when it launched the HBCU libraries website (www.hbculibraries.org) in

February 2002.That same year, the alliance acquired support from the

Council on Libraries and Information Resources (CLIR) and SOLINET, later

known as LYRASIS. Support from SOLINET/LYRASIS was especially

instrumental in helping the alliance to achieve its aims, as, with the

help of Kate Nevins and the LYRASIS Board of Trustees, the organization

was able to hire Jennifer Bliss to serve as Project Coordinator for the

HBCULA as it commenced its work. Bliss coordinated the inaugural meeting

of the HBCULA held in October 2002 in Atlanta, Georgia, and LYRASIS also

provided most of the funding to support the meeting. Once again, library

directors and deans from 103 HBCUs gathered at the meeting to discuss

the unique challenges faced by their institutions and brainstorm how

they might collaborate on mutually beneficial projects that would

strengthen library programs and services, as well as bolster their

presence and visibility on their campuses.

By 2003, the alliance had created and passed bylaws and established the

first official list of HBCU libraries, deans, and directors, and the

group officially adopted the name “HBCU Library Alliance.” The

organization, in collaboration with LYRASIS, also received a grant in

the amount of $160,000 from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to conduct a

needs assessment and develop programs. The HBCULA was also able to hire

its first Program Officer, Lillian Lewis, former Deputy Executive

Director of the Association of Specialized and Cooperative Library

Agencies (ASCLA) and the Reference and User Services Association (RUSA)

of the American Library Association. Lewis provided the administrative

support and management necessary for the organization’s programs in

digitization, leadership, and marketing. In 2005, the Alliance was

incorporated as a 501©3, which then positioned the organization for the

direct receipt of funding. In 2003, the first Board of Directors was

elected by the body: Janice R. Franklin (Alabama State University);

Tommy Holton (Dillard University); Loretta Parham (AUC Woodruff

Library); Emma Bradford Perry (Southern University and A&M College);

Elsie Stephens Weatherington (Virginia State University); Yildiz

Brinkley (Tennessee State University); Zenobia Blackmon (H. Councill

Trenholm State Technical College); Karen McDaniel (Kentucky State

University); and Anita Moore (Rust College). The initial roster of

officers for the Alliance was also selected. These efforts and successes

in securing funding then allowed the HBCULA to create numerous projects

that have had real impact upon the individual libraries and colleges and

universities associated with the libraries, as well as faculty, library

staff, students, and scholars conducting research and using information

resources and African American primary resources. A final significant

moment for the HBCULA occurred with the creation of the “Preserving the

Story” project. This project demonstrated the Alliance’s internal

capacity to manage a proposal.

Activities in Digitization and Preservation

In its inaugural meeting held in October 2002, the HBCU Library Alliance

drafted a document called “A Call for Cooperation among HBCU Libraries:

Opportunities for Consideration,” which served as a manifesto that would

guide how the organization would proceed from that moment in fulfilling

its purpose of strengthening programs and services at HBCU libraries.

One strategic charge that this document placed on the Alliance was to

focus its collaborative work in the areas of preserving and providing

wider access to the culturally relevant materials collected and held at

HBCU libraries. Acknowledging that “HBCU libraries hold rich collections

of books, photographs, pamphlets, newspapers, letters, and other

cultural materials” that are “of significant value to faculty,

researchers, students, and society as a whole,” the Alliance then began

devising projects that would preserve and conserve these materials, as

well as make them more easily accessible both physically and digitally.

To that end, the HBCULA formed a partnership with the Cornell University

Library, which had received a grant of $400,000 from the Andrew W.

Mellon Foundation to help train HBCU archivists, librarians, and other

library staff to digitize their collections and produce web-based

searchable databases of these materials that would be of great value to

researchers. This partnership, the HBCU-Cornell University Library (HBCU-CUL)

Digitization Initiative, was an eighteen-month nationwide program that

provided participants with a digital imaging training workshop and

sessions that addressed concerns about hardware and software and

copyright issues, offering information on how best to preserve

collections once they were digitized. Through the HBCU-CUL Digitization

project, the HBCULA also created a website for hosting project documents

and an email list to serve as a communications tool for project members.

Through a competitive application process, ten HBCU libraries were

selected as participants based on a number of factors, including the

commitment their institutions were willing to make to the project, the

richness of their institutional holdings, and the assurance of diversity

in representation of types and geographical locations of the libraries.

The institutions selected to become part of the initiative were Alabama

State University, Bennett College for Women, Fisk University, Grambling

State University, Hampton University, the Robert W. Woodruff Library of

the Atlanta University Center, representing the consortium of Atlanta

HBCUs (where the server for hosting the digital collection is located),

Southern University A&M College-Baton Rouge, Tennessee State University,

Tuskegee University, and Virginia State University. Production of the

initial digital collection began in 2006 and was completed by 2007, by

which time 3,519 items had been digitized (Cornell University Library,

2007).

Perhaps what was most unique about this project was the Alliance’s

efforts to promote and publicize its work in the mainstream media. A

press release about the initiative generated by Cornell University

Library staff reached BlackPR.com, and details about the project spread

to 150 African American media outlets such as newspapers, radio, and

television. In September 2005, Ira Revels, a Cornell University

librarian who was intimately involved with the HBCULA-CUL Digitization

project, was a guest on a national program on XM Satellite Radio, “Mind

Yo Business,” where she was able to discuss the project to radio

listeners. Furthermore, The Crisis magazine published an article titled

“HBCUs Digitize Black Experience” in its November/December 2006 issue

(Cornell University Library, 2007). The media interest in the HBCULA-CUL

Digitization Initiative illustrates the positive nature of the work of

the Alliance and the essential work it is doing to preserve the African

American cultural heritage for future generations.

While digitization efforts like the HBCU-CUL Digitization project

utilize new technologies to ensure continued access to historical

materials and make them accessible to a global audience, physical

preservation of the original materials that have been digitized or of

those items that are too fragile to be preserved in this way is also

essential to ensure the photographs’ long-term survival. Photographs in

particular seem to be highly vulnerable to destruction when not properly

cared for. To that end, in 2007, the Alliance formed a partnership with

the Art Conservation Department of the University of Delaware Library,

the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts (CCAHA),the Image

Permanence Institute(IPI), and LYRASIS in a project aimed particularly

at safeguarding the unique photographic materials held at HBCU

libraries. Prior to the beginning of this undertaking, only 22 percent

of all HBCU libraries had performed conservation assessments of their

photographic collections, an essential step in determining both the

short- and long-term conservation needs of their collections. Thus this

project was vital in assisting HBCU libraries with taking the necessary

steps needed to bring their photographic preservation efforts up to date

so that they could better manage, as LYRASIS Executive Director Kate

Nevins expressed, the collections that “document the visual and

institutional history and legacy of HBCUs and form a core of primary

research material for the study of African American history (L. Parham,

personal communication 2011).

The endeavor, which was called the “Preservation of Photographic

Collections at Historically Black Colleges and Universities Project,”

began with a training session for thirty HBCU archivists and librarians

and three staff members held at the University of Delaware in 2007 (HBCU

Library Alliance, 2006). In this workshop, participants received

training not only on photographic preservation, but they also received

onsite collection assessments and information about environmental

monitoring to ensure the longevity of their photographic collections.

Additionally, these archivists and librarians received information on

how to apply for funding to assist in their preservation efforts. In the

second phase of this project, a team of five conservation experts from

the University of Delaware and the CCAHA served as consultants and

visited 10 HBCU libraries to provide advice and help libraries

understand their most pressing conservation needs and priorities. These

consultations then aided the libraries when they pursued support for

collection projects from the project’s HBCULA Preservation Steering

Committee. From these requests, the steering committee selected projects

from ten libraries for implementation during phase three of the project.

The outcomes of this Photographic Preservation project have been

impressive and will have far-reaching consequences for the future. As

the individual institutions began examining their collections, they

found hidden treasures in their midst that have generated renewed

interest in their libraries on their campuses. For instance, Hampton

University’s library noted that, as a result of their participation in

this project, there has been a renewal of “considerable

interdisciplinary interest across the campus,” with several departments

implementing an oral history series to help expand the collection.

Lincoln University’s library found that their project has increased the

appeal of their photographic collection to genealogists (Cornell

University Library, 2007) . As with the HBCU-CUL Digitization

Initiative, the Alliance also made outreach efforts to publicize their

work to a wider audience than the institutions that participated in the

project. In 2009, Alliance members gave a panel presentation at the 2009

HBCU Week conference, sponsored by the White House Initiative on HBCUs,

which allowed them the opportunity to target top-level administrators

and raise an awareness of the preservation needs at HBCU libraries,

archives, and museums. The project was a great success, as by its

culmination in 2009, 31,675 photographs were rehoused and the

Photographic Project’s collection had grown by 66% from its start. The

participants in the project also noted other benefits of their work in

this area, which included an increase in their confidence in the

principles of archival management, ability to identify photographic

format and projects, and an increasing knowledge of best practices for

housing and exhibiting photographic materials (Cornell University

Library, 2007).

Impacting Librarianship through Training

In addition to executing these valuable projects in digitization and

conservation, perhaps the area where the HBCULA has made its greatest

accomplishments has been in training. At the outset of the creation of

the Alliance, many HBCU librarians, as Loretta Parham and Janice

Franklin recount, often encountered the message from other librarians

that HBCUs were not professional places to work. To counter this

negative stereotype, the HBCULA felt that it was imperative to put in

place programs that would help develop strong leaders for HBCU libraries

who would in turn change these adverse perceptions and entice talented

staff to consider careers at their institutions. The Alliance learned

that many librarians working at HBCUs often did not attend professional

meetings of organizations such as the ALA (American Library Association)

or ACRL (Association of College and Research Libraries) because of

limited resources. Therefore, the HBCULA devised a series of leadership

institutes designed to provide both theoretical and practical training

for these librarians and library directors. Commencing in 2005 in

partnership with SOLINET and funded by a two-year grant of $500,000 from

the Mellon Foundation, these leadership institutes were created with the

goal of imparting valuable resources to participants and encouraging

library staff to develop their capacities for leadership on their

respective campuses, the larger HBCU library community, and the field of

librarianship in general. The Alliance also hoped that the institutes

would give participants assistance with strategies to more fully

integrate information literacy and library services into existing

teaching and learning activities and courses on their campuses. Offering

these opportunities in the “backyards” of so many HBCU campuses

contributed significantly to the overall success of the program.

Twenty-three libraries joined in the first leadership institute, which

was held in 2005, and was comprised of face-to-face training sessions, a

librarian exchange program, site visits, and training on mentorship,

networking, and advocacy over the course of two years. All participants

were required to create projects that they would work on as part of

their participation in the institute; in 2006, the twenty-three library

directors reconvened to share the results of these projects with each

other. With

the assistance of subsequent grants from the Mellon Foundation, the

leadership institutes have continued since 2005, with participants

creating projects each year that illustrate the very real impact that

the institutes have had on their individual libraries. The knowledge,

skills, and motivation the librarians receive from the institutes have

led them to develop ingenious ways to increase their libraries’

relevance in the lives of their students, faculty, and campus

administrators in today’s changing academic landscape. For example,

librarians at Langston University founded a Family Literacy program to

assist student parents with managing their time and resources to better

balance their educational and family commitments. This project takes

serious consideration of how much the background of the “typical”

American college student has changed. Other librarians reported

increasing their campus visibility by partnering with faculty or other

campus organizations for instructional purposes, for humanities

programming, and for initiatives to improve institutional rates for

recruitment and retention of students and faculty. Not only have these

staff members noticed how perceptions of their libraries have changed on

their campuses, but they have also felt the leadership institutes’

impact upon their personal careers. Dawn Kight, manager of library

systems and technology at Southern University and A&M College of Baton

Rouge, related that the institute taught her to utilize networking more

effectively and has enhanced the performance and visibility of her

library team at her institution.

In addition to the leadership institutes, the Alliance has also created

other training opportunities that will have an impact on the field of

librarianship in the future. Its exchange program, for instance,

provided opportunities for HBCU librarians to spend time at academic

libraries located at predominantly white institutions (PWI) and test

their ideas to help foster programs or to change the methods of

providing services at their home institutions. Morgan Montgomery, a

librarian at Claflin University, credits the time she spent at East

Carolina University library in Greenville, North Carolina, with

assisting her in gaining knowledge on how to create an Information

Literacy Program and how to use Skype as an effective virtual delivery

tool for reference services at Claflin (Brooks-Tatum, 2013).

The HBCULA has also instituted training designed to attract college

students to the library and archival professions. For instance, in the

second phase of the HBCULA-University of Delaware Photographic

Preservation Project, student interns participated in a one-week summer

institute in photographic preservation at the University of Delaware.

The interns received training on the value and significance of

photography; nineteenth-century photographic print materials; cyanotype

print production; and several other pertinent topics. This training may,

in turn, lead these students to seek careers in librarianship or

archival work in the future, possibly leading to new generations of

leaders for HBCU libraries.

Research, Conferences, and Outreach Efforts and Collaborations

A key area of the Alliance’s work has been focused on research because,

as mentioned above, scholarship on HBCU libraries has not been robust.

In partnership with LYRASIS and with additional funding provided by the

Mellon Foundation, the HBCULA undertook research to analyze the

challenges faced by HBCU libraries, producing two reports in 2005 and

2011, entitled “State of HBCU Libraries,” documenting its findings.

Utilizing data collected from 193 academic libraries, 93 of which were

HBCUs, gathered by the National Commission on Libraries and Information

Science and the National Center for Educational Statistics, the reports

compared how HBCU libraries stood in comparison to non-HBCU libraries on

issues such as number of library staff, staff salaries, budgets,

funding, and expenditures. Compiling this data and making these

comparisons, the Alliance believed, would allow members to “take action

to strengthen support of their libraries, individually and as a group”

(Nyberg and Idelman, 2005).

The findings promulgated by both the 2005 and 2011 “State of HBCU

Libraries” reports have had and will continue to have long-reaching

consequences for HBCU libraries, for they illustrate both what HBCU

libraries are doing well and the real deficits and challenges that these

libraries face in comparison with their peer institutions. For instance,

the reports show that while HBCU libraries had a higher average number

of library staff who hold MLS degrees per 100 full-time students than

non-HBCU libraries, the average annual salaries for professional library

staff, both those with and without the MLS degree, was $7,885 less than

the average salary for similar staff at the non-HBCUs in the study.

Additionally, while libraries across the board have suffered

significantly from budget cuts because of reductions of state and

federal funding, non-HBCU libraries were able to expend almost double

the amount of money on library acquisitions ($2,870,352) than HBCU

libraries ($1,411,7911) were (Askew and Phoenix, 2011). The research

conducted to compile these two reports has provided essential evidence

for HBCU libraries to advocate for increased funding and support from

their institutions. Mary Jo Fayoyin, Library Dean at Savannah State

University, and her staff attest that they were able to receive

additional financial and institutional assistance for the Asa Gordon

Library from sharing the report’s findings with university

administrators.

In addition to the promotion of research on HBCU libraries through the

“State of HBCU Libraries” reports, the HBCULA has also successfully

marketed its ten-year accomplishments through a Mellon-funded project

called Preserving The Story. This project is designed to highlight the

various successes of the member institution libraries. Looking at the

stories published as part of this series, one can conclude that these

libraries have transformed the way they conduct their work and interact

with students and faculty on their campuses, transformations that are,

in part, the result of key initiatives in digitization, preservation and

conservation, leadership development, and information literacy that were

fomented by the HBCULA. Nine of the libraries’ stories were also

published in the journals American Libraries and Against the Grain

(O'Brien and Franklin, 2004).

Other ways the Alliance positively impacts the profession has been

through continuous meetings and collaborations that allow the member

institutions frequent opportunities to interact with each other, share

updates and celebrate their progress with various projects, and

brainstorm on the future direction of the organization. The 100

libraries that comprise the HBCULA have met on a biennial basis since

2006. In homage to its African American cultural background, the

Alliance has instituted a tradition where membership meetings begin with

a roll call in which institutions are announced and their library staff

stand in recognition in order of the institutions’ founding date, all

done with an accompanying background of djembe drumming to promote a

sense of kinship and identity amongst members. The Alliance uses its

biennial meetings to conduct HBCULA-sponsored workshops, mini-training

sessions, and share updates on projects such as those involving

preservation and digitization projects. All in all, these meetings

provide vital opportunities for the members to communicate with each

other and to share knowledge, skills, and professional insights that

members can incorporate into operations at their respective campuses.

Impact of the HCBCULA: Looking Toward the Future

In just over a decade, the HBCULA has made real, impactful achievements

that have changed the way that libraries at these institutions have

functioned and has had significant effects on the students, faculty, and

researchers that these libraries serve. The Alliance has become a strong

voice for HBCU institutions and has formed significant partnerships with

other organizations, such as LYRASIS, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation,

the University of Delaware, the HBCU Faculty Development Network, and

the White House Initiative on HBCUs. The HBCULA’s work has increased the

connectivity its libraries have with the larger HBCU community and,

through its successful marketing efforts, improved the visibility of

HBCUs both nationally and globally. Many of these accomplishments are

recorded in the Preserving The Story project, illustrating how the

member libraries have made changes in the key areas that were identified

as crucial in the HBCULA’s document “Call for Cooperation among HBCU

Libraries.”

Looking at some of the stories illustrates how successful members have

been in achieving these aims. The Alliance’s leadership institutes have

been instrumental in aiding in the promotions of several librarians from

within the HBCU network to the position of library director. Kentucky

State University library reported that it has incorporated QR codes into

its catalog, thereby becoming a leader in the state of Kentucky in

incorporating this leading technology as a new method of user access. In

keeping with the alliance’s emphasis upon preservation, Elizabeth City

State University’s library successfully applied for and received several

grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to preserve

its university archives. Along those same lines, Fisk University is

making a major promotional push to publicize their organization and

preservation of its important “Julius Rosenwald Rural Negro Schools”

archives, a collection that highlights a significant aspect of African

American educational history in the United States. Other libraries have

made strides in information literacy training, such as Tennessee State

University’s initiatives to train both low-income youth and public

librarians in internet usage and Johnson C. Smith’s PALS (Promoting

Active Library Services) program that incorporates Web 2.0 technology

and library technology to attract new users to the library.

Under the current leadership of Sandra Phoenix, who serves as Executive

Director of the HBCULA, the Alliance has devised new projects that

continue its previous work. The Alliance received its second direct

grant award from the Andrew W. Mellon foundation for a project entitled

“Expanding Library Support for Faculty Research in HBCUs.” Working in

partnership with the HBCU Faculty Development Network, the Alliance will

use the funding from this grant to assess and strengthen library

services to support faculty research at HBCUs. This project is designed

to foster improved library services on the individual campuses of HBCUs

and develop collaborative approaches to expand library support for

faculty research. In keeping with its emphasis upon training and

attracting new talent to the library profession, the Alliance has also

formed a partnership with Wayne State University for a program called

“Librarians for the 21stCentury.” The purpose of this project is to

construct an online Master of Library Science (MLS) program to educate

students from underrepresented groups to increase diversity in the

library profession. The HBCULA’s role in the project is to recruit

qualified applicants for the online MLS program from a pool of both

undergraduates attending HBCU institutions and library paraprofessionals

who are currently employed at HBCU libraries. The Alliance will also

select senior librarians who have participated in its own leadership

program to serve as mentors for the students. In this way, the HBCULA

hopes to continue to have significant impact upon programs, services,

and training offered at member institutions and to change the profession

of librarianship at large, countering negative stereotypes about the

professionalism of these institutions (L. Parham, personal

communication, 2011).

Looking back at the HBCULA’s decade of accomplishments, its achievements

in narrowing the digital divide that separates the rich and the poor in

this country should be celebrated. Yet its positive impact and

groundbreaking work is not without continuing challenges. As the faculty

at the nation’s 105 Historically Black Colleges and Universities face

shifting paradigms in the way they conduct both their teaching and their

research, libraries and librarians must devise new ways to support the

faculty’s work, as well as the broader research agendas that many

academic institutions are forming. Preservation of historical artifacts

associated with HBCUs has become much more of an essential aspect of

library and archival work as HBCUs become threatened with either closure

or the possibilities of merging with other colleges as part of

cost-saving efforts. As the only library organization that is uniquely

dedicated to serving HBCUs, the Historically Black Colleges and

Universities Library Alliance more than ever will find that it has an

important and essential role to play in the academic landscape as it

advances its mission to educate future generations and serve as a

repository for the rich cultural and historical heritage of people of

African descent in the United States and the Caribbean. Table 2

REFERENCES

HBCU Library Alliance, "Historically Black Colleges and University

Library Alliance."Last modified 2006.Accessed August 30, 2013.

http://www.hbculibraries.org/index.html.

HBCU Library Alliance (2006). “A Call for Cooperation among HCBCU

Libraries: Opportunities for Consideration.” (HBCU Library Alliance

2006).

Askew and Phoenix (2011). “Executive Summary: The State of Libraries at

Historically Black Colleges and Universities,” 2011.

Brooks-Tatum, Shanesha RF (2013). "Claflin University Implements

Successful Information Literacy Program." Against the Grain, 02 2012.

http://www.hbculibraries.org/images/board/HBCU_Feat_v24-1.pdf (accessed

August 30, 2013).

Cornell University Library (2007). "Final Report to the Andrew W. Mellon

Foundation on Building Collections, Building Services, and Building

Sustainability: A Collaborative Model for the HBCU Library Alliance."

Last modified 09 2007. Accessed August 30, 2013.

http://www.hbculibraries.org/docs/Final_report.pdf.

Freeman, Geoffrey T (2000). “The Academic Library in the 21st Century:

Partner in Education” in Building Libraries for the 21st Century: The

Shape of Information. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2000.

Interview with Loretta Parham by Shanesha Tatum Brooks, June, 2011.

Interview with Kate Nevins by Shanesha Tatum Brooks, December 14, 2011,

Atlanta, GA.

Nyberg and Idelman (2005). “Executive Summary: State of HBCU Libraries

Report,” 2005.

O’Brien PL, Janice RF (2004). “Preserving a Historic Legacy: The HBCU

Library Alliance.” Against the Grain Magazine, February 2004 Feature, p.

1-19.

Parham L, Janice RF, Kate N (2006). “The HBCU Library Alliance and

SOLINET: Partners in Inclusion” in Barbara I. Dewey and Loretta Parham

(eds.), Achieving Diversity: A How-To-Do-It Manual for Librarians. New

York: Neal-Schuman, 2006, p. 182 - X.

Submitted: January 4, 2014

Accepted: January 19, 2014

All the contents of this

journal, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution License

|

|